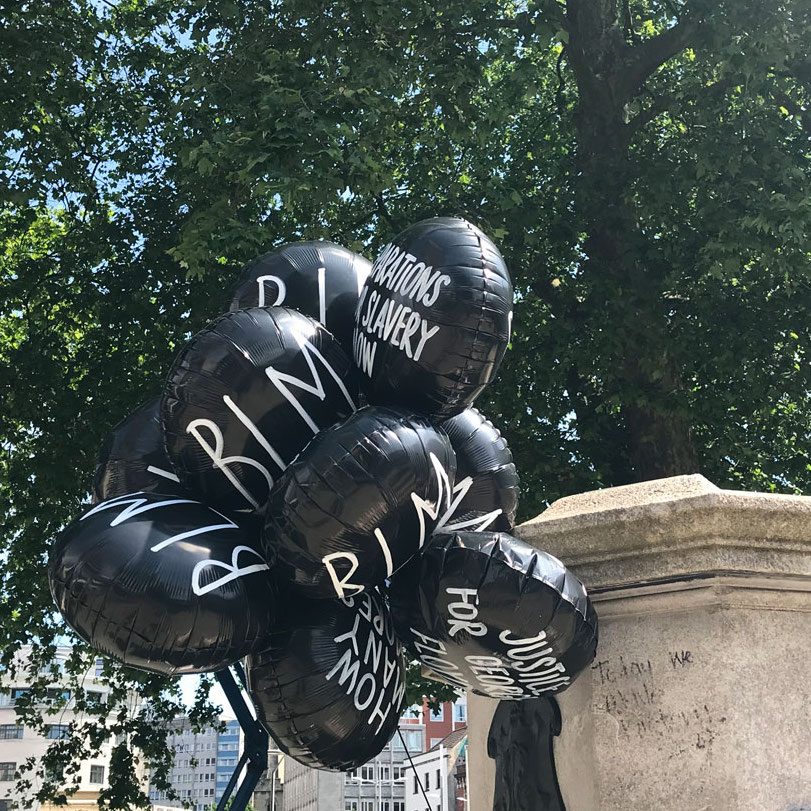

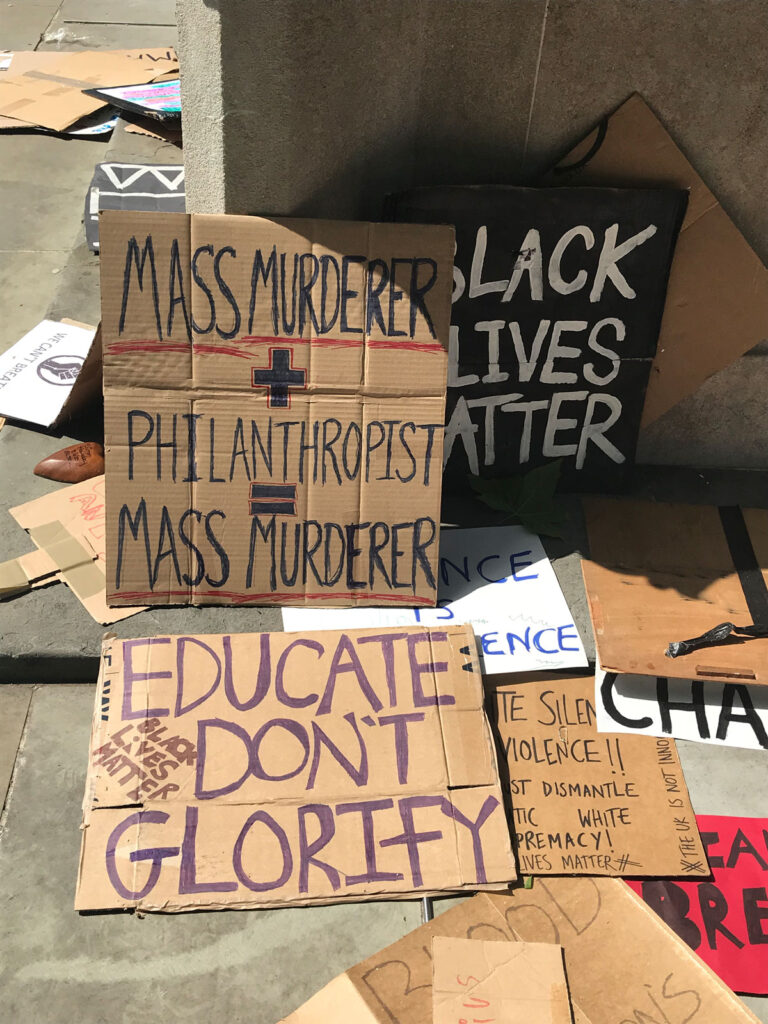

As Bristol Quakers we are proud of the role which our antecedents played in the abolition of slavery. It is a well-known fact that Quakers were at the forefront of the British abolition movement from the 1780s onwards. Meeting for Sufferings (the Quaker national council) pledged its opposition to the slave trade in 1783 and most members of the first national Abolition Committee were Quakers. It is also widely known that Bristol was Britain’s leading slave port in the first half of the eighteenth century. However, some Friends may be surprised and dismayed to learn how many local Quaker fortunes were the direct or indirect outcome of links to slavery. In response to Black Lives Matter, and after Colston’s downfall, it feels necessary to acknowledge this unattractive aspect of Quaker history.

A starting point might be the building of the splendid Quaker Meeting House at Quakers Friars in 1747. Historian Madge Dresser reveals that ‘Eight of the twenty largest contributors to Bristol’s new Quaker Meeting House… were by 1755 also members of the newly formed Society of Merchants Trading to Africa’ (Slavery Obscured, 2001, p.131). Some Bristol Quakers were directly involved in ‘the Negro trade’, as owners of slave ships. In the 1760s (forty years after Philadelphia Quakers had agreed to discipline such activity), the tide of Bristol Quaker opinion started to turn against slave trading. The Bristol Quaker Men’s Meeting recorded enquiries into its members’ involvement in the Africa trade in 1761 and 1785. However this growing concern did not deter Quakers from continuing to deal in slave-produced goods from the West Indies and America. Some became wealthy through supplying slavers with essential ironware and the brass manillas (armlets) which became an unofficial currency on the West African coast, whilst others helped finance the slave economy through Quaker banks.

The beautiful terraces of Clifton were built in the era of Bristol’s slave trade. It is sad to find that those who invested in these elegant new homes included Quakers who had profited from slavery. Terry Townsend’s Bristol and Clifton Slave Trade Trails (2016) provides detailed evidence. Investors in Royal York Crescent included the Quaker merchant and iron manufacturer Joseph Harford, alongside others with African or West Indian links. Goldney Hall was the home of two famous Quaker families – the Goldneys and then the Frys. The Goldneys made their money as grocers dealing in slave-produced sugar, before moving on to run the Warmley Brass Works and invest in Abraham Darby’s Coalbrookdale ironworks. Darby’s Baptist Mills Brass Works, founded in 1702, produced manillas for the Africa trade. The Fry family also started out as grocers, before learning to manufacture chocolate from West Indian sugar and cocoa beans. The Eltons of Clevedon Court had diverse manufacturing interests, including links with fellow-Quakers Darby and the Goldneys. By 1748 ‘the family owned the slaver Constantine… which set sale for the Gold Coast and transported 240 slaves to Jamaica’ (Peter Martin and Isioma Nwokolo, Bristol Slavers, 2014, p.27). Other Bristol Quaker families with connections to slavery included the Champions (who owned West Indian ships and took over Darby’s Brass Works), the Galtons (exporting guns to West Africa), the Lloyds (trading, banking and plantation ownership) and William Reeve and Corsely Rogers (both trading slaves to South Carolina).

The beautiful terraces of Clifton were built in the era of Bristol’s slave trade. It is sad to find that those who invested in these elegant new homes included Quakers who had profited from slavery. Terry Townsend’s Bristol and Clifton Slave Trade Trails (2016) provides detailed evidence. Investors in Royal York Crescent included the Quaker merchant and iron manufacturer Joseph Harford, alongside others with African or West Indian links. Goldney Hall was the home of two famous Quaker families – the Goldneys and then the Frys. The Goldneys made their money as grocers dealing in slave-produced sugar, before moving on to run the Warmley Brass Works and invest in Abraham Darby’s Coalbrookdale ironworks. Darby’s Baptist Mills Brass Works, founded in 1702, produced manillas for the Africa trade. The Fry family also started out as grocers, before learning to manufacture chocolate from West Indian sugar and cocoa beans. The Eltons of Clevedon Court had diverse manufacturing interests, including links with fellow-Quakers Darby and the Goldneys. By 1748 ‘the family owned the slaver Constantine… which set sale for the Gold Coast and transported 240 slaves to Jamaica’ (Peter Martin and Isioma Nwokolo, Bristol Slavers, 2014, p.27). Other Bristol Quaker families with connections to slavery included the Champions (who owned West Indian ships and took over Darby’s Brass Works), the Galtons (exporting guns to West Africa), the Lloyds (trading, banking and plantation ownership) and William Reeve and Corsely Rogers (both trading slaves to South Carolina).

It is something of a relief to find that these same Bristol Quaker families eventually also included prominent supporters of the anti-slavery movement. They did not surrender their slavery-related wealth, but they often turned their influence to good purpose. According to Martin and Nwokolo, the Quaker banker John Harford rebuilt Blaise Castle ‘with profits from the slave trade’ in 1796. Yet Joseph Harford had been the first chairman of the Bristol Committee for the Abolition of Slavery eight years earlier and John Harford junior became a friend and ally of William Wilberforce during the latter stages of the campaign. Quakers were the first to welcome the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson to Bristol in the 1780s, and female campaigners included Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck (nee Galton) as well as the redoubtable Hannah More. Members of the Goldney family also joined the abolition movement. Quakers were hopefully absent from the long list of Bristol slave owners who benefited from more than £2 million compensation when British slavery was finally abolished in 1833.

Julia Bush